The Land of Lila

Storia del Nuovo Cognome / The Story of a New Name

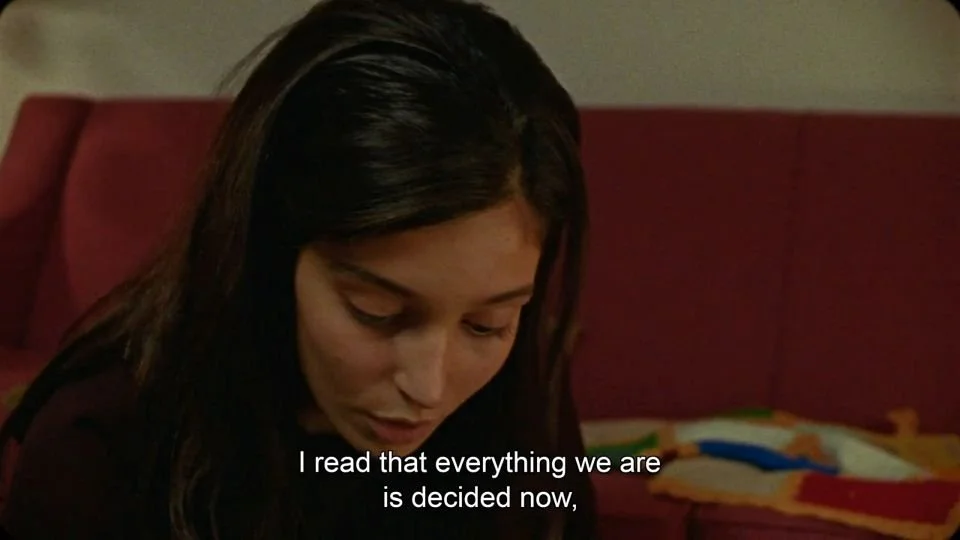

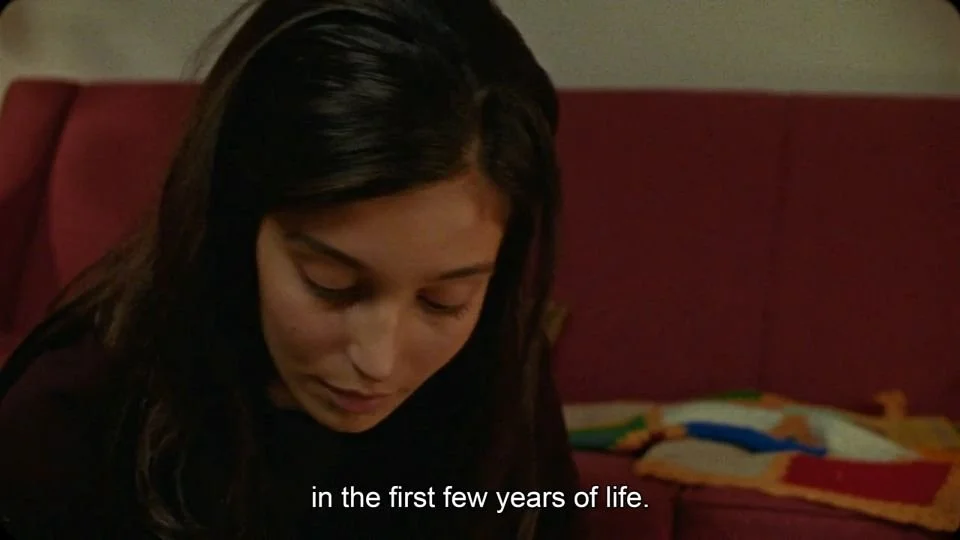

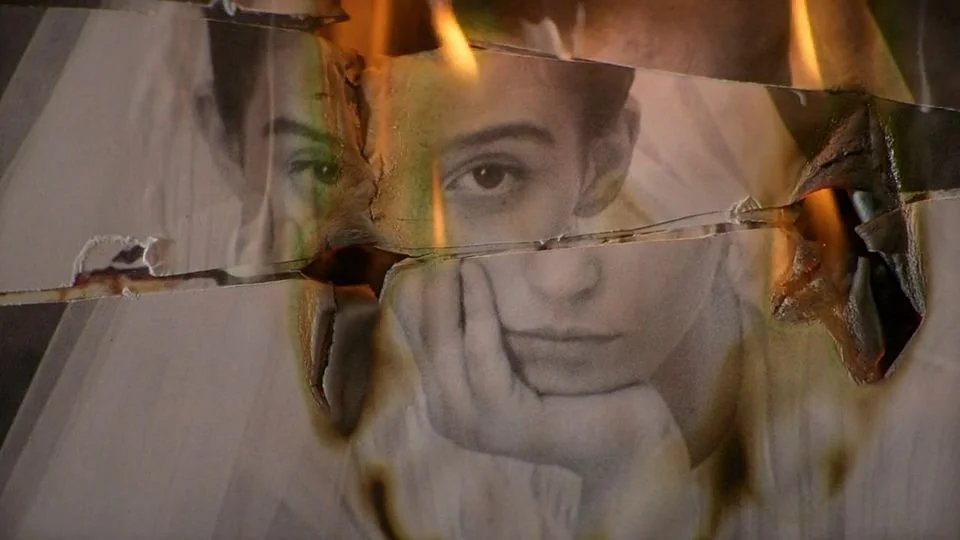

Raffaella ‘Lila’ Cerullo, My Brilliant Friend. Season 2.

Eight years into this multidisciplinary project—one where I research, I write, I go back and forth between the US and my homelands, I do field work, I remember, I share stories, I archive, I document on film, I draw, I paint, I collect and sow seeds, I follow some force much bigger and greater than myself with the plants by my side, not always fully understanding in real time what the end game is, but nevertheless following my nose, my gut—and then I weave these fragments together, drawing connections between things, through each of the medicines and art works I make, co-conspiring with the plants on storied medicine for the times. As my work and I continue to spiral outward and evolve, I knew it was time to embrace a more open and expansive name that really speaks to the many threads of this work and can encapsulate the many directions this project will take.

On the surface, The Land of Lila, is an ode to the Earth, my motherlands, and my favorite literary character. But as those of you familiar with my work know, I like to dig deep. My culture speaks in layers and so do I. What follows are the layers of my practice, this evolving project, and the story of a new name.

My Brilliant Friend. Season 1.

“I felt all the fascination of the way Lila governed the imagination of others or set it free, at will, with just a few words: that speaking, stopping, letting images and emotions go without adding anything else. I’m wrong, I said to myself in confusion, to write as I’ve done until now, recording everything I know. I should write the way she speaks, leave abysses, construct bridges and not finish them, force the reader to establish the flow.”

Elena Ferrante, The Story of the Lost Child. Translated by Ann Goldstein.

Raffaella ‘Lila’ Cerullo, My Brilliant Friend. Season 1.

Raffaella ‘Lila’ Cerullo

Lila is not just a nickname but a variation of her actual nickname, Lina, that only those closest to her used, often shortened to just Li.

Dad on 35mm

I have a Li in my life too, my dad. His real name was Arturo but he, too, preferred to be called a variation of his nickname by those closest to him–Li.

It was never even a question why Ferrante chose to remain behind the scenes—when I first was connected with her books years ago, I only wished I too would have afforded myself that same anonymity and therefore freedom.

While the main outward focus of my work over the last 7-8 years has been the seasonal medicine boxes, the internal foundation and focus has been, and will always be two fold–a deep connection to the Earth, and an equally deep desire to create Art. Deep connection maybe isn’t even the right way to put it–ever since I can remember, I have felt, understood, that the Earth is alive, is a body, and that my body, all our bodies, come from this body, are this body. The Land of Lila is an acknowledgment of this connection–the terrain of land as the Earth body, the terrain of our bodies as the Earth. This enduring inextricable link is at the heart of my politics, ethics, ideas about health, and how I choose to practice as an herbalist. What happens to the Earth body is simultaneously happening to our bodies and true health can only be measured collectively–we will never truly be well as individuals in this deeply sick world of our making where, by and large, humans treat the Earth as an object to extract from and exploit, with no real regard for the consequences to the living beings of this planet, including ourselves. As Silvia Federici stated in Re-Enchanting the World, when speaking of the ongoing enclosures of the Earth and the new enclosures of our own bodies: “Thus tired earthly commons, the gift of billions of years of laborless transformation, meet tired human bodies.”

"You And I Are Earth”, 1661. Creator unknown. Found in a London sewer. Tin-glazed earthenware plate. Collection of the Museum of London.

There is a thread through all my work, which I continue to be pulled by and in turn pull on, that draws me further, deeper, into the subterranean artisan lineage from which I come and am a part of.

A few years ago I began a body of Art Work–Into the Night–which I have committed to working on over a long period of time. It’s an excavation of sorts, exploring submerged histories, feminist fairy tales, folklore, the depth in darkness, memory as an archive. Night is a strong thread–Night as in dark, dark as in the necessary place where life forms, where truth reveals itself, where people can be themselves–my motherlands are another. While I love every inch of our Earth, I cannot deny the sacred bond I feel with the lands of my ancestors–lands where the necessity of diversity is on full display, where multiculturalism is the true history and an ethic for those of us in communion with our home. These lands are often invoked to describe many human phenomena. Campania, where some of my family comes from, has long been known as the land of the Tammorra frame drum, as well as the land of Witches and Wolves. As a whole nation, Italy has also long been referred to as the land of machismo, particularly in regard to the numerous hyper patriarchal aspects of the culture and its incredibly late reform of fascist era rape laws in 1996, as well as its continual issues of domestic and gender-based violence and femicide.

Mamma Etna in progress, 2022.

And of course, there are De Martino’s writings on Italy as the land of remorse, and as a microcosm for the entire world, that have stuck with me and along with the many other titles these lands have been given, have inserted themselves into my own name choice—

“In the narrowest sense, The Land of Remorse is Apulia, inasmuch as this is the elective area of tarantism—a historical-religious phenomenon which developed in the Middle Ages and continued to the eighteenth century and beyond, to the present relics still usefully observable in the Salentine Peninsula. Tarantism is a “minor,” predominantly peasant religious formation, although at one time it involved the upper classes, too; it is characterized by the symbolism of the taranta which bites and poisons, as well as the symbolism of music, dance, and colors which deliver its victim from the poisoned bite. In a wider sense, though, the Land of Remorse—the land of a wretched past which returns and regurgitates and oppresses with its regurgitation—is Southern Italy, or more precisely the lands of what was the old Kingdom of Naples. This was a kingdom which, hemmed in between the Papal States and the sea, suggested to one of its kings the image of a land shielded from history and nearly outside of this world, “between holy water and salt water,” between the patrimony of St. Peter and the sea. The Land of Remorse aspires to be a molecular contribution to a religious and cultural history of our South, in the prospect of a new dimension of the Southern Question. This means that the molecular phenomenon from which the historical discourse takes its cue—tarantism—is not considered in its local isolation (in which case it would be vain to attempt to insert it into a history). Rather, tarantism is first of all examined here in its genesis and persistence in a fully Christian epoch; second, in the way in which Catholicism, natural magic, Enlightenment reason and positivism all reacted to it; and finally, the way in which we ourselves can react to it, within a historicism and humanism which are increasingly sensitive to everything concerning “remorse,” the return of the wretched past, the past that was not chosen. For in a third and still broader sense, The Land of Remorse is our whole planet, or at least that part of it which has entered the shadow-cone of its wretched past.”

—Ernesto de Martino, The Land of Remorse: A Study of Southern Italian Tarantism

My Brilliant Friend. Season 1.

From the beginning of this project in 2018, I have made and stuck to the decision to work jobs alongside this, my real work. There’s so many reasons for this—first off… I just love it too much. Art and working with the Earth is just too important to me, it feels wrong to have my main motivation be anything other than true desire and love. I need the freedom to be inspired more so by that deep inner and outer voice than by the pressure to bring in a certain amount of money. Currently, I see a lot of people who identify as artists acting in ways that don’t align with my own ethics—commodifying every and anything to make a living, turning cultural and folk practices into products and services, selling the idea of community, grasping for power and authority, taking advantage of others hunger for connection just to make a buck. Traditional jobs are tough and largely underpaid and I understand why so many are so desperate to avoid them. But I also deeply question people who are able to carve out an existence where they don’t really have to interface with the realities of our time, especially those who also claim they have wisdom and insights to share with us from their isolated and privileged standpoint. In an attempt to secure a way out for ourselves, too many of us are running little businesses as individuals, taking on what should be the work of a team all by themselves and not being honest about the toll it takes. Even as someone who chooses to keep this as primarily a passion project, I have overworked myself and violated my own boundaries around work countless times and am dreaming of and working on ways to continue making my work more communal, not more individualized. At a time when everyone is a self-proclaimed teacher, coach, proprietor, content creator, making bullshit just to monetize online, selling courses and tours, doubling down despite the deep inequality and affordability crises we are experiencing—I have chosen a different path.

I’ve worked with children for most of my adult life and these experiences, in different educational environments, has added a rich layer to my life that informs my own work. I’ve had profound experiences in the shittiest of workplaces–in moments of camaraderie between coworkers, in encouraging people to advocate for themselves and to talk openly about our salaries, and in the countless observations of the brilliance of children and the acknowledgment of the importance of treating them with dignity and respect. It feels important to me to work in the community I live in, to remain involved in the actual day to day life of the majority of humans on this Earth rather than separating myself from it all.

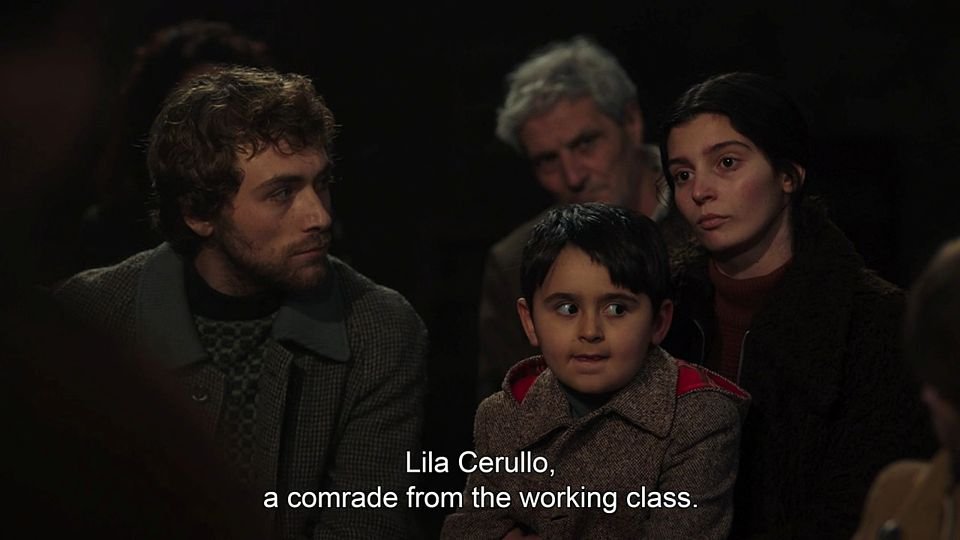

Raffaella ‘Lila’ Cerullo, My Brilliant Friend. Season 2.

In the article “Disasters at the Origin of the Sense of Disaster”: Ferrante on Fascism, Tessa Brown discusses the politics of the Neapolitan Novels and offers this passage and explanation on the grounded and admirable ethics of Lila:

“Does Ferrante offer any recourse to a society facing a rise of fascism? If she does point to solutions, they do not come from men; whether dealing with fascists or communists, the girls find that “you had to hide everything from men,” whose possessive and competitive compulsions only caused trouble. If anything, Ferrante offers glimpses of what can happen when women take responsibility for one another. Elena begins to grasp this, in Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, when she is organizing with her sister-in-law, Mariarosa, and other local leftists. The night she meets Mariarosa at an organizing meeting, Elena ends up staying with her, and Elena, Mariarosa, and a young mother, Silvia, end the evening listening to two men bloviate, a situation Elena analogizes as “drowsy heifers waiting for the two bulls to complete the testing of their powers.” As Silvia’s baby begins to cry, Elena’s thoughts drift to Lila, to her analytical power, to a wish that Lila was there with her. Then suddenly, she recognizes how Lila would see the present situation.

I heard her saying: If you are silent, if you let only the two of them speak, if you behave like an apartment plant, at least give that girl a hand, think what it means to have a small child. It was a confusion of space and time, of distant moods. I jumped up, I took the child from Silvia gently and carefully, and she was glad to let me.

Lila’s genius — a genius shared by Marxists and novelists both — is her attention to the realities of material life, her refusal to be hoodwinked by abstract theories, her insistence on the observable complexities of the here and now….

As a brilliant novelist, Ferrante’s writing is never pedantic, but roots politics and history in the emotions of the individual person — the choice to help, for example, or the choice to look away. If the climax of all four novels is the upheaval at the sausage factory, its emotional climax comes in the next scene, in a quiet moment inside Elena that, as a student of politics and of literature, continues to astonish me. Ruminating over Pasquale and Nadia’s criticisms, wondering if she’s done wrong or right, Elena makes the decision, in her heart, to detach. “Had I acted badly? Should I have left Lila in trouble? Never again, never again would I lift a finger for anyone. I departed, I went to get married.” In this moment of resignation, Elena makes a choice — the wrong choice. Faced with criticism she finds too difficult to bear, she decides, not to evolve, but to leave. For the real-life Ferrante, an author we will never know, Lila is a literary tool that ties bourgeois existence back to working-class realities — the realities of poverty, of exploitation, of sexual violence. If we can take any lesson from Elena and Lila, it is to stay connected to the Lila inside all of us — the neighborhood girl who refuses to abandon injustice — who chooses to stay, and to fight.”

My Brilliant Friend. Season 3.

For anyone who is not familiar with this story, this article Those Who Study and Those Who Know written by Dawn Tefft gives a good concise overview of the bildungsroman and its central themes.

“You have to come back, we need you.” But Lila shook her head uneasily, she repeated to Nadia: I have the child, and pointed to him, and to Gennaro she said, Say hello to the lady, tell her you know how to read and write, let her hear how you speak. And since Gennaro hid his face against her neck while Nadia smiled vaguely but didn’t seem to notice him, she said again to her: I have the child, I work eight hours a day not counting overtime, people in my situation want only to sleep at night. She left in a daze, with the impression of having exposed herself too fully to people who, yes, were good-hearted but who, even if they understood it in the abstract, in the concrete couldn’t understand a thing. I know—it stayed in her head without becoming a sound—I know what a comfortable life full of good intentions means, you can’t even imagine what real misery is.”

Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, Elena Ferrante. Translated by Ann Goldstein.

Raffaella ‘Lila’ Cerullo, My Brilliant Friend. Season 4.

Lila is a dark mother of our world, a peasant sibyl who chooses to see clearly and speak truthfully, to resist the temptation of giving in to the multitude of corrupt forces wreaking havoc on Earth, to remain an underdog and resist oppression hand in hand with others.

A bit on Sibyl’s from Lucia Chiavola Birnbaum’s Black Madonnas:

“Joyce Lussu, a world war II partisan and feminist, has written a study of the Appenine sybil, for whom i monti Sibillini in the Marche are named. Near the sanctuary of the black madonna of Loreto, whose facade of Mary’s everyday dwelling inside the church depicts ten sibyls standing before ten male Jewish prophets, Lussu explored her native region. Coming upon an abandoned town in the mountains, she found traces of an ancient sibylline civilization at Cerreto.

“Sybilline,” for Lussu, connotes the values of the goddess as they persisted in peasant culture. Romans, invading Germans, and christian bishops tried to destroy this culture, she says; later, its women were persecuted as witches.

“Una sibilla?” What does it mean, Lussu asked an old woman she found in the ancient town. Her own mother, said the crone, had been a sibyl in Cerreto thirty centuries ago. “The sibyls who lived before us are all our mothers. Their memory becomes ours, in a continual cycle…of past and future.” Sibyls, in Lussu’s view, are all our mothers and all our daughters who keep the memory of the prehistoric peaceful civilization and envision a future communitarian democracy wherein people share ethical and social responsibilities in a society in close rapport with nature. Sibyls point to the submerged culture of women, the cultura sommersa of women storytellers who remember and envision, in her words, a world “without bosses and without wars.”

Raffaella ‘Lila’ Cerullo, My Brilliant Friend. Season 4.

As humans who have forgotten their ecological place continue to ravage the Earth and convince us all that this is how it has always been and will always be, there is a much truer, older story living beneath the surface. We need only to look in the places that too often go overlooked, are purposely hidden or dismissed, to seek out the dark mothers around and in all of us. Abandon the tired, ahistorical heroes journey narrative and tap into the much bigger, deeper, vast story we are all creating together.

As Ferrante said when asked a question about Lila:

“Do you worry that a figure from your past might attempt to affix your life in print the way that Lila experiences with Elena?

Ferrante: I love figures like Lila: they come into the world precisely to show us that stability, security, certainty, ones own happiness are imagined dreams, while the truth engulfs us.”

Season 3.

PAINT

Lotions and scents, ripe figs,

raw silk, the cat’s striped pelt…

Fat marbles the universe.

I want to be a faint pencil line

under the important words,

the ones that tell the truth.

Chase Twichell

Season 2.